Presented by

+

+

Piñon Country, a conservation photography exhibit from Christina M. Selby Photography and Santa Fe Botanical Garden. This online exhibit is adapted from and complements the physical touring exhibition. All artwork and photos (c) Christina M. Selby except where noted.

WELCOME TO PIÑON COUNTRY

Make it stand out

It all begins with an idea. Maybe you want to launch a business. Maybe you want to turn a hobby into something more. Or maybe you have a creative project to share with the world. Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

On rugged mesas and rolling mountainsides throughout the intermountain West, piñon and juniper trees grow where few other trees can survive. Humble by almost any standard, they gnarly, stumpy stature has rarely inspired poetry or exhalation like the heights of Redwoods or Ceibas present in other parts of the Americas. And yet, those of us that live in this rugged “Piñon Country” know that piñons and their companions the hardy juniper, are the lifeblood of these arid states.

Piñons are tied to Native American origin stories where Pinyon Jays, the iconic “Blue Crow” of the Southwest, also makes appearances. Pinyon Jays evolved in tandem with piñons over millennia, making them uniquely adapted to the West. Economies are built on piñon nuts and fuelwood. The leaves, bark and berries of junipers fill traditional herbal medicine chests. The ancient skeletal branches of juniper trees and trunks of piñons frame many of the West’s most iconic landscapes inspiring wonder and awe. Author Gary Nabhan ranked “Piñon Nut Nation” of equal importance as Salmon Nation in regional food traditions. Life thrives here because of the abundance the woodland produces.

Facing a future of change, this rugged and resilient woodland provides inspiration for reimagining our relationship to this landscape and ultimately, our western identity.

THE WOODLAND

Rugged. Resilient. Reimagined.

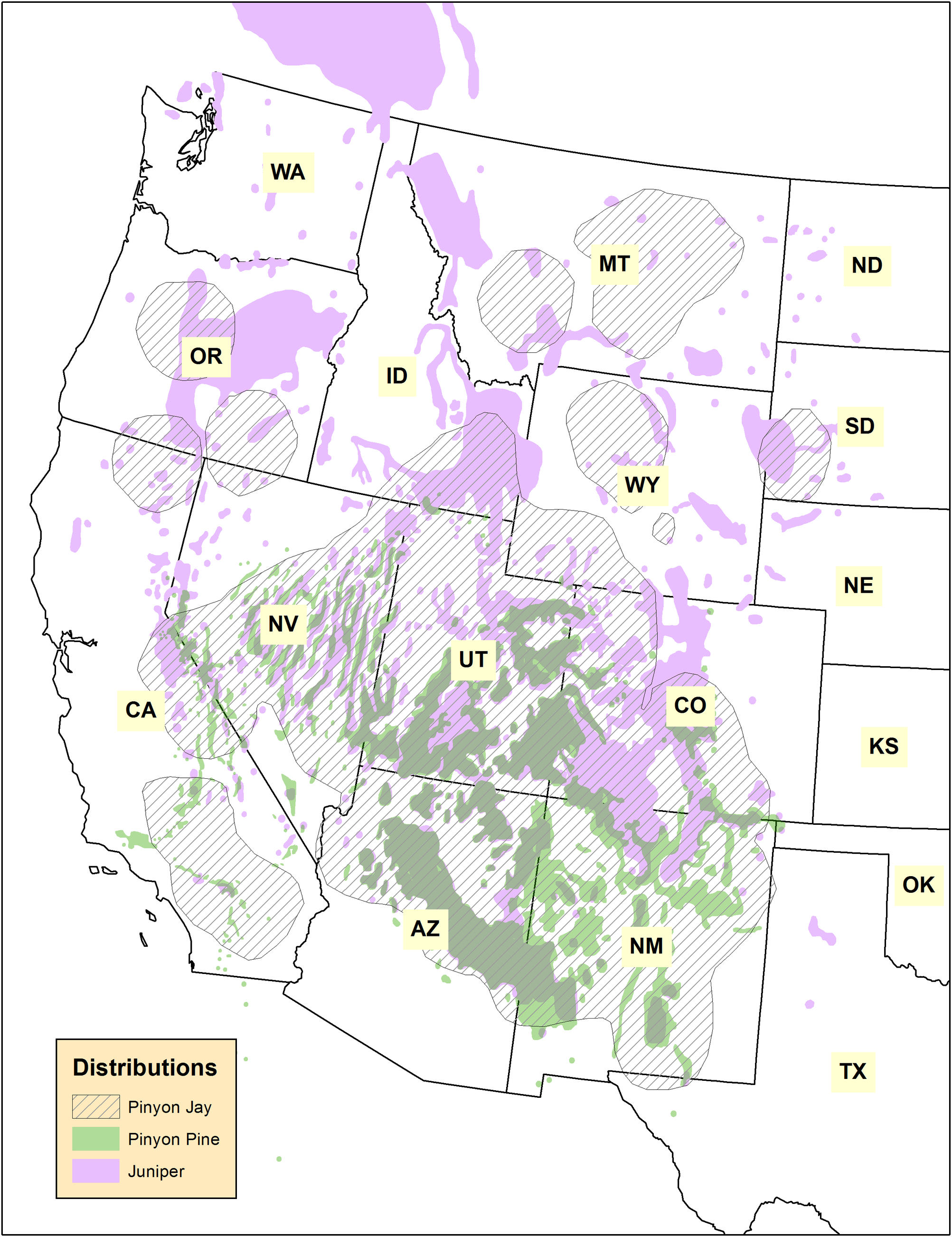

Piñon-Juniper woodlands are essential, if undervalued, forests of the interior West. Forming belts around arid mountains, rooting in rugged canyons, sprouting from red desert soils, they cover 15% of the land in five states: New Mexico, Utah, Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, and to a lesser extent inhabit Wyoming, Montana, South Dakota, California, Texas and Baja California. Some of the West’s most iconic places like the Grand Canyon, Zion National Park, Bryce Canyon, the Great Sand Dunes, Mesa Verde, and the Rio Grande Gorge all belong to Piñon Country.

This woodland provides a wealth of resources and ecosystem services, from wildlife habitat and vegetative cover for watershed protection, to piñon nuts and fuelwood. The woodlands are home to millions of urban and rural people and have been a resource and home to indigenous peoples for thousands of years.

“Piñons and junipers are the size of humans. We don’t look down at them, casually, and we don’t gaze up in awe. We are equal in scale…They have the reserved warmth of a Native grandmother. When you live in piñon-juniper woodland, you live with the trees, not under them. You participate, you reside.”

- Stephen Trimble, Southwestern Writer & Photographer

Living Soil

Cryptobiotic soil (biocrust for short) is the craggy, often dark or burnt looking carpet stretching between shrubs and grasses in arid lands. It’s actually the desert’s skin—a community of living organisms such as algae, lichens, fungi, mosses and cyanobacteria that live on the soil surface of drylands. The presence of biocrust is an indicator of a healthy piñon-juniper ecosystem where it keeps soil in place, holds moisture, and regulates soil temperatures. Biological soil crust is the lifeline of arid lands because it plays a vital role in soil stability, moisture, and nutrient cycles. Without it, nothing can grow and the plant and animal life that rely on this, like piñon trees and pinyon jays, would not survive. Mature biocrusts can take thousands of years to develop. This small piece of biocrust pictured here may be centuries old. These soil crusts are very fragile and easily damaged by trampling. Help protect the health of our arid lands: don’t bust the crust!

Red box = cyanobacteria

Yellow box = lichen

Blue box = moss

Orange box = soil crust

More than 70 species of birds are known to breed in piñon-juniper woodland and they support one of the highest proportions of obligate or semi-obligate bird species among forest types in the West. More than in other forest types, birds, in particular, are critical to the dispersal of the seeds of piñon and juniper trees, the dominant tree species in this ecosystem.

THE SECRET LIVES OF PINYON JAYS

Pinyon Jays and piñon pines share an intimate relationship. The cerulean corvids live in the trees year-round, nesting in their branches and eating piñon seeds. In return, the birds disperse seeds, helping the trees proliferate. But drought, beetle infestations, and warming temperatures have pushed both species into a snowballing decline. Over the past 40 years the Pinyon Jay population has shrunk by 85 percent across its range from Baja California to Wyoming, spurring the nonprofit Defenders of Wildlife to petition for a federal endangered species listing in April 2022. By studying the piñon ecosystem, researchers hope to help the trees, jays, and other vulnerable birds that reside in the habitat.

The gregarious Pinyon Jay, known by the folk name Blue Crow, evolved over thousands of years in tandem with the piñon pine, closely tied to the life cycle of these coniferous trees.

This crestless jay of southwestern pine and juniper forests is the only representative of its genus, Gymnorhinus, which means "bare nostrils." Unlike many of its close relatives such as the Scrub Jay and Common Raven, the Pinyon Jay lacks feathers at the base of its bill to cover its nostrils. This anatomical difference means that the bird can probe sticky pine cones for seeds — a staple of its diet — without coating feathers with sap.

Green cones…

Seed dispersal…

Nesting colonies…

Social behaviors - flocks, mates, creches

THE PIÑON PUZZLE (THREATS)

HOW CAN I HELP?

You can help protects Pinyon Jays and their habitat! Every person can make a difference.

Although the specific reasons for this decline remain unclear, it is likely that Pinyon trees are suffering from long-term drought, increasing temperatures, and other climatic shifts. Research suggests that these changes are leading to piñon pines that produce fewer nuts. The birds seem to be ranging further from historic colony sites and might be relying more heavily on other food sources such as juniper berries and insects. Meanwhile, land managers find themselves in a double bind needing to both preserve grasslands and protect Pinyon Jay habitat. Guidelines for grassland preservation with an eye to the jay are lacking.

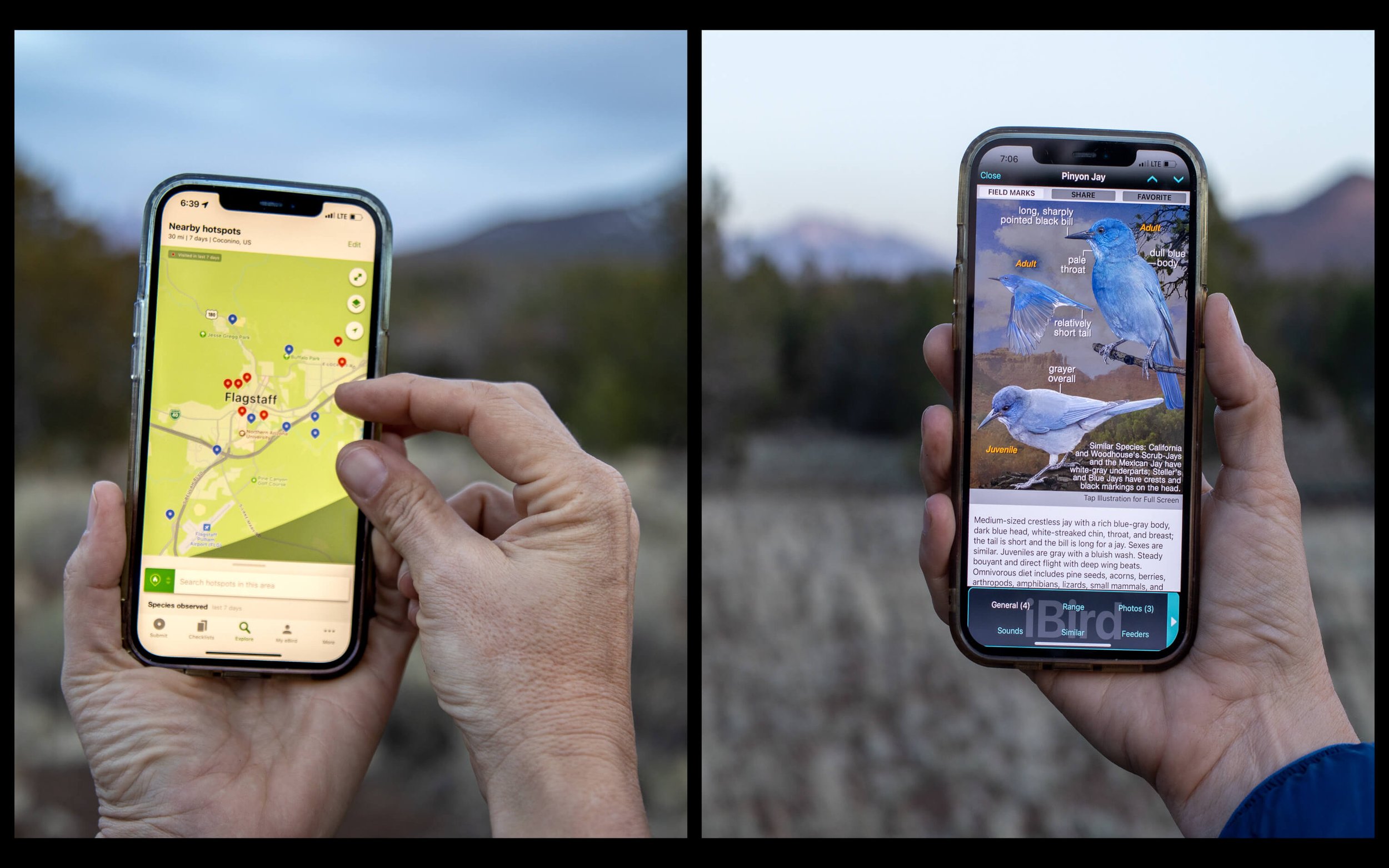

Help researchers better understand how Pinyon Jays use the piñon-juniper landscape.

You can play an important part in reversing these trends by helping to collect new data about Pinyon Jays and their habitats. Learn how to get involved below.

COLLECT DATA ON PINYON JAYS

COLLECT DATA ON PIÑON PINES

CARE FOR THE HABITAT IN YOUR YARD

ABOUT THE PHOTOGRAPHER

Christina Selby is a conservation photographer, science writer, and naturalist based in Santa Fe, New Mexico who uses the power of visual and narrative storytelling to enchant people's hearts and inspire action on behalf of nature.

The Piñon Country project began during the pandemic as an desire to get to know the birds and animals in the landscape around my home in Santa Fe where I live surrounded by piñon-juniper trees and grasslands. After almost two decades of living on the quiet edge of town, large new housing developments were sprouting up all around me to meet the increasing demand in Santa Fe. The piñon and juniper savannah were being replaced by tall apartment buildings, concrete, and non-native urban trees. I wondered what would become of my wild neighbors: the coyotes, prairie dogs, ravens, and other birds.

On a chilly February day, I set out with my camera to explore a small patch of public land near my home. Walking through a fresh layer of snow, I encountered a small flock of Pinyon Jays foraging under a lone piñon tree junipers. I attempted to hide in a cluster of trees to watch them when a single Pinyon Jay landed on the branch above me and started calling out my presence to its flock. Sitting within touching distance, the jay looked directly into my eyes from above as if to say: you are fooling no one. I was immediately enamored with their charisma, intelligence, funny strut as they searched for food on the ground, and unique social calls and chatter between the group.

Upon returning home, I researched the jays further and learned of their intimate relationship with piñon pines and their rapidly declining numbers. Having never recognized the presence of Pinyon Jays before this experience, I began getting glimpses of them: visiting the tall cottonwood outside my office, flying over as I hiked among piñon pines, as if to say, here we are, when will you tell our story? Listening to the signals that nature was sending me, I began spending more time exploring the piñon-juniper woodland in New Mexico and beyond. I reached out to environmental groups and scientists to understand the conservation concerns about the Pinyon Jays and spent time in the field learning about the decades long history of research to understand the lives of Pinyon Jays.

I traveled to central New Mexico to see the impact of new wind farms on the piñon-juniper landscape. I stopped at a old, run-down gas station where on a graffitied wall a jay was painted. As I contemplated the art, a truck carrying carrying the wing of a wind turbine passed on one side while a train hauling containers of oil and gas sped by on the other. I knew that without awareness of their presence and importance to the piñon-juniper landscape and proper siting, those energy developments could destroy the nesting colony of Pinyon Jays and contribute to their decline. I decided then that I would take on telling their story and the story of their habitat so we could make better decisions and learn to co-exist with these amazing, intelligent, social birds.

Collaborating with environmental groups and scientists, I set out to document the lives of Pinyon Jays, understand the ecosystem they play a key role in, and raise the awareness and value of Piñon Country in the west and my place in this community. Little did I know that initial encounter with Pinyon Jays was a rare moment and due to their nomadic nature, moving across large territories, they wouldn’t be so easy to find again. After two years of working on this project, I feel I’ve only scratched the surface of sharing the essence of this place and the lives of Pinyon Jays. My search for Pinyon Jays has since taken me all across the Southwest and the wall-of-green, which is how I used to experience the piñon-juniper landscape, has become a rich, diverse habitat full of life, wonder, enchantment and story. It is an journey I will continue for a long while to come. I now feel privileged to count my self as a member of Piñon Country and I invite you to join me on this journey.

Christina is the author of two nature guidebooks and producer of the documentary film Saving Beauty. Her editorial photographs and writing have appeared in Audubon Magazine, bioGraphic, Scientific American, National Geographic online, Outdoor Photographer, New Mexico Magazine, The Open Notebook, and Mongabay. Using conventional photographic techniques along with camera traps, timelapse, and drones, she works closely with field biologists to both effectively and ethically photograph some of the most imperiled species and ecosystems on the planet while also highlighting the threats they face and the conservation efforts on their behalf. Christina has a bachelor’s in Ecology & Evolution and a master’s in Environment & Community. She is an award-winning photographer, and member of Her Wild Vision, League of Conservation Writers, and the International League of Conservation Photographers.